En ce moment au Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper :

Et découvrez cette magnifique et très sensible vidéo réalisée par sa fille en mémoire de ce grand peintre :

Caroline Bouteiller-Laurens, Art Questions

Histoire de l'Art, Art History

En ce moment au Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper :

Et découvrez cette magnifique et très sensible vidéo réalisée par sa fille en mémoire de ce grand peintre :

A drawing of the Pylos Combat Agate. Courtesy of Ben Gardner/the University of Cincinnati.

By Sarah Cascone, November 8, 2017

It’s the tomb that keeps on giving. More than two years since its discovery, a treasure-filled Greek tomb has offered up perhaps its most significant find to date: a Minoan stone carving so sophisticated and detailed that it has forced art historians to reaccess their understanding of ancient artwork.

Dubbed the Pylos Combat Agate, the sealstone carving is just an inch and a half wide, but its impact on the study of prehistoric art may well be enormous.

“This seal should be included in all forthcoming art history texts, and will change the way that prehistoric art is viewed,” said Sharon Stocker, a senior research associate in the University of Cincinnati classics department, in a statement. She believes the stone, made by the ancient Minoans, is the finest-known example of prehistoric glyptic art produced in the Aegean Bronze Age.

The intricately carved gemstone “shows that the [Minoan’s] ability and interest in representational art, particularly movement and human anatomy, is beyond what it was imagined to be,” added her husband, department head Jack Davis, a professor of Greek archaeology. “The representation of the human body is at a level of detail and musculature that one doesn’t find again until the Classical period of Greek art 1,000 years later.”

“Looking at the image for the first time was a very moving experience, and it still is,” Stocker noted. “It’s brought some people to tears.”

The Pylos Combat Agate. Photo courtesy of Jeff Vanderpool/the University of Cincinnati.

The Pylos Combat Agate. Photo courtesy of Jeff Vanderpool/the University of Cincinnati.

The landmark find shows a warrior battling against two adversaries, killing one enemy, the other already dead at his feet.

It’s the latest archaeological treasure to come out of the Griffin Warrior Tomb, discovered by the Davis- and Stocker-led team from the University of Cincinnati at Pylos in 2015, which was touted as the most significant Greek archaeological discovery in half a century.

The tomb is believed to have been the final resting place of a remarkably wealthy Mycenaean warrior or priest. (A team of specialists has since recreated his probable appearance based on the dead man’s skull.)

The Griffin warrior was buried around 1500 BC, about the time that the Mycenaeans, from mainland Greece, defeated the Minoans, a more advanced civilization from the island of Crete that had a massive influence on the Greek world. The presence of many Minoan artifacts in the tomb suggests a previously unknown degree of exchange between the two cultures.

To date, archaeologists have catalogued some 3,000 burial objects from the Griffin Warrior Tomb, including a bronze sword with a gold-embellished ivory hilt; four solid gold rings; silver cups; over 1,000 carnelian, amethyst, jasper, and agate beads; fine-toothed ivory combs; and a golden dagger.

“The whole tomb contains such a wealth of riches that it’s really very stunning,” Stocker told artnet News. “It’s extremely rare to find a tomb that wasn’t looted during antiquity or in modern times.” Amid the treasures, the seal, heavily encrusted with limestone that took over a year to clean, was almost overlooked, a tiny, apparently insignificant object.

The Pylos Combat Agate before it was cleaned. Photo courtesy of Alexandros Zokos/the University of Cincinnati.

The Pylos Combat Agate before it was cleaned. Photo courtesy of Alexandros Zokos/the University of Cincinnati.

“It was after cleaning, during the process of drawing and photography, that our excitement slowly rose as we gradually came to realize that we had unearthed a masterpiece,” wrote Stocker and Davis in the journal Hesperia, according to the New York Times.

“The Pylos Combat Agate is one of the finest objects that we have found in the Griffin Warrior tomb,” Stocker added. “The craftsmanship is something that you rarely see in the Minoan and Mycenean world. It’s virtually unparalleled.”

The fine details on the stone carving, made all the more difficult to decipher by banding in the agate stone, are so minute that some of them, as small as a half a millimeter in length, can only be seen with the assistance of magnification. Davis described the artwork as “incomprehensibly small.”

In Crete, such sealstones would be used to make impressions that would mark ownership. Placed on a bottle of wine, for instance, it would indicate that the seal was unbroken. In contrast, the Myceneans treated such sealstones as decorative objects, wearing them as jewelry. The Griffin Warrior was found sporting another sealstone pendant as a bracelet.

Less is known about how such an object might have been made, as there is no evidence of magnification at existing archaeological sites for sealstone workshops in Crete. Theories include the use of rock crystal, or artisans with exceptional close-up vision, perhaps due to nearsightedness. Agate is also quite hard, making it difficult to carve.

“It is indeed a mystery how they did it,” said Stocker. “It’s amazing to hold and look at it.”

If Johannes Vermeer used a camera obscura, a new book may have figured out how he did it.

Detail from Jan Vermeer’s Young Woman With A Pearl Necklace, (1662-1665). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Detail from Jan Vermeer’s Young Woman With A Pearl Necklace, (1662-1665). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

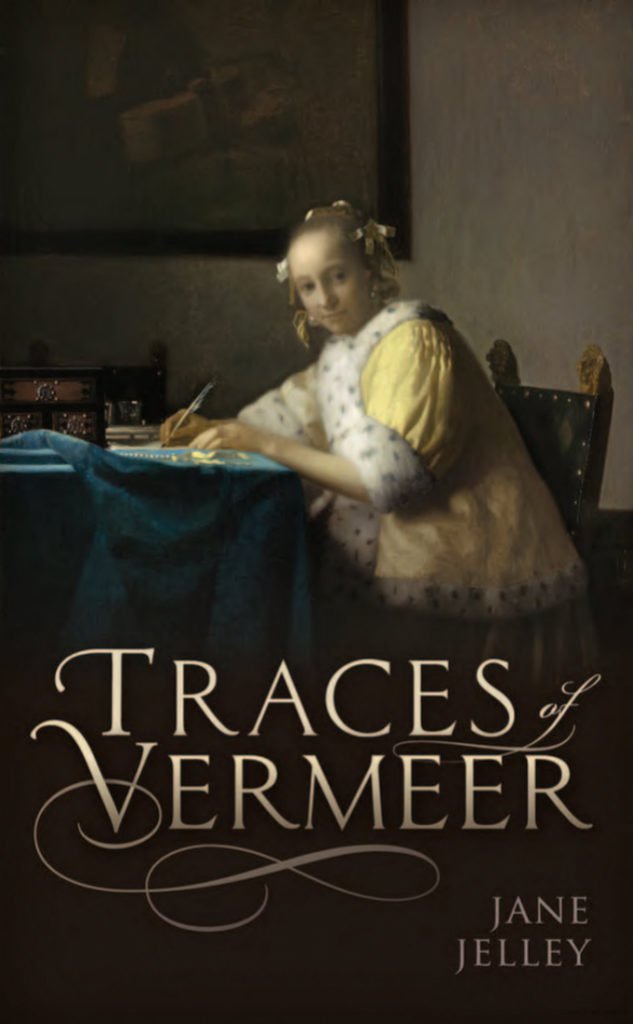

Leaving behind just 36 exquisite, immaculately lit paintings, Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer has captivated art lovers for generations. Now, author Jane Jelley may have uncovered the artist’s secrets. In her new book, Traces of Vermeer, Jelley tests long-held suspicions that Vermeer actually traced his compositions using a camera obscura—by demonstrating just how such a technique could have been executed.

For over a century, art historians have wondered if Vermeer could have been working with the aid of a camera obscura, a pinhole device that uses a lens to project an inverted view of a subject into a darkened space. And if so, how did the artist convert an upside-down light projection into a fixed painting?

Precious little is known about the Dutch Golden Age master, aside from his birthplace in Delft. So there is no historical evidence supporting such theories. All we have are the paintings and what can be inferred from their appearance.

Jane Jelley, Traces of Vermeer (2017), cover. Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

Jelley, a painter, has approached the mystery from the point of view of an artist, doing her best to replicate Vermeer’s work from the canvas up, based on X-ray observations.

Beneath the surface, there aren’t underdrawings on Vermeer’s canvases, and there are no signs that he made corrections to his layouts as he worked. Instead, he created a shadowy image outlining the scene before painting. These unusual underpaintings served as a foundation for his luminous works.

Using a camera obscura, Jelley attempted to come up with the same underlayer through a rudimentary monoprint process. She projected images of various Vermeer works through the lens, then traced each image in dark paint on a sheet of transparent oiled paper. She then pressed the painted paper—essentially an image negative—down on canvas, producing a rough outline of each scene. The results appear remarkably similar to the underpaintings of the Vermeer works.

Jane Jelley devised a means of making prints from a tracing made using a camera obscura, as part of the research for her new book Traces of Vermeer (2017). Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

In reimagining Vermeer’s process, Jelley made certain to use a method the artist could have employed in his era. “The materials used in the studio experiments were all available in Vermeer’s time. Great care was taken to prepare the surface of the canvas in a way he would have recognized; and pigments were ground by hand into cold pressed linseed oil,” Jelley wrote on her website, describing the process. “This experiment took a year to complete not only because grounds had to be dry and prepared ready to receive a print, but also because it took time to refine a successful technique.”

If Vermeer really did use this method, it would go a long way to explaining his distorted proportions and off-center compositions. It’s also easy not to have to adjust your perspective when you’ve traced it all in one fell swoop.

L: Jane Jelley made this print based on Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring using a camera obscura, as part of the research for her new book Traces of Vermeer (2017). R: Jelley added color to the print, based on Vermeer’s original. Images courtesy of Oxford University Press.

The first person to raise the possibility that Vermeer used a camera obscura was American artist Joseph Pennell, who in 1891 noticed that the man in the foreground of Officer and Laughing Girl was shown nearly twice as large as the girl he sat facing, in much the same way that such a scene might appear in a photograph.

In 2002, Philip Steadman further explored this theory in Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth Behind the Masterpieces. (It was a lecture by Steadman in 2007 that inspired Jelley to begin the research that led to Traces of Vermeer.)

Johannes Vermeer,

Officer and Laughing Girl (c. 1655–60). Courtesy of the Frick Collection, New York.

Artist David Hockney also famously made his case on the matter, with help with from physicist Charles Falco, in their 2001 book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. To further his point, Hockney made a number of portraits using the techniques he claimed were employed by the likes of Vermeer.

In her book, Jelley is quick to allay fears that Vermeer’s use of the camera obscura diminishes his genius. Rather, she says, it is an impressive innovation. “The image from the camera obscura is merely a projection. To capture and transfer this to canvas requires skill, judgment, and time; and its product can only ever be part of the process of making a painting,” she writes. “We can never know if Vermeer worked this way; but we should remember that this is not a mindless process, and not a shortcut to success.”

Source : Did Vermeer Trace His Golden Age Masterpieces? An Artist Puts the Theory to the Test | artnet News

If you thought Piet Mondrian’s art was all abstract geometric forms and primary colours, a new exhibition in the Gemeentemuseum will have you reconsidering this notion. Upon entering the first room, you spot the still life of a dead hare and faithful recreation of an early morning view of Amsterdam’s famed Singel canal.

The next few halls continue in the same vein, showing dozens of bucolic and, at first glance, traditional landscapes and depictions of the sea, dunes and windmills. In total some 300 of the artist’s works – a quarter of his entire output and almost the entirety of the museum’s Mondrian collection – are on show in the exhibition titled ‘The Discovery of Mondrian.’ Many of them have never seen before by the public, but rediscovered by the museum staff during a massive restoration project between 2009 and 2015.

The little-known early work is important believes curator Hans Janssen, as it shows just how innovative and modern the artist truly was.’ He speaks of the ‘sense of depth’ that carried through to his later work, the visibly sophisticated brushwork techniques (‘the working of the paint’) but also of something else: ‘At first glance some of them look like 19th century rubbish but they have a quality that is very hard to describe and that has to do with a sense of inner self’. Indeed there is a sense of quiet spirituality and optimism that is a constant in all the work, as well as a potent luminosity that lifts the work out of the mundane. (…)

Read more : The Discovery of Mondrian at The Gemeentemuseum | Wallpaper*

Exposition du Collectif Multi-Prises

Du 09/06/2017 au 23/07/2017 de 14h00 à 19h00

Exposition Galerie du Faouëdic, 2 boulevard général Leclerc 56100 Lorient, 02 97 02 22 57

L’association Multi-Prises a carte blanche pour s’emparer des murs de la galerie du Faouëdic en proposant une installation immersive. L’exposition vient en contrepoint d’un projet artistique mené auprès des élèves des classes à horaires aménagés musique et danse du collège Anita Conti, en partenariat avec le conservatoire de Lorient.Artistes du collectif engagés dans ce projet : Simon Augade, Thomas Daveluy, Nicolas Desverronières, Nastasja Duthois, Arnaud Goualou, Sylvain Le Corre, Jérémy Leudet, Claire Vergnolle.

Consulter le site du collectif Multi-Prises : http://multi-prises.fr/association/

Du 9 juin au 23 juillet

Du mercredi au dimanche

De 14h à 19h à la galerie du Faouëdic.

Visites commentées par les artistes

11 juin à 17h

4 juillet à 12h30

22 juillet à 17h

Entrée libre