Entrée de l’exposition Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 9, 2020 – May 9, 2020. © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: John Wronn

Le Museum of Modern Art a développé très tôt des liens profonds avec la photographe Dorothea LANGE (1895-1965). Elle contribue à la toute première exposition de photographie du musée en 1940 et participe à la préparation de sa première rétrospective, qui ouvrira en 1966, trois mois après sa mort. La modernité de son œil et son parti pris engagé n’ont pas pris une ride et, dans les salles de vente comme dans les galeries de musée, ses mots-images continuent de résonner.

Words and Pictures

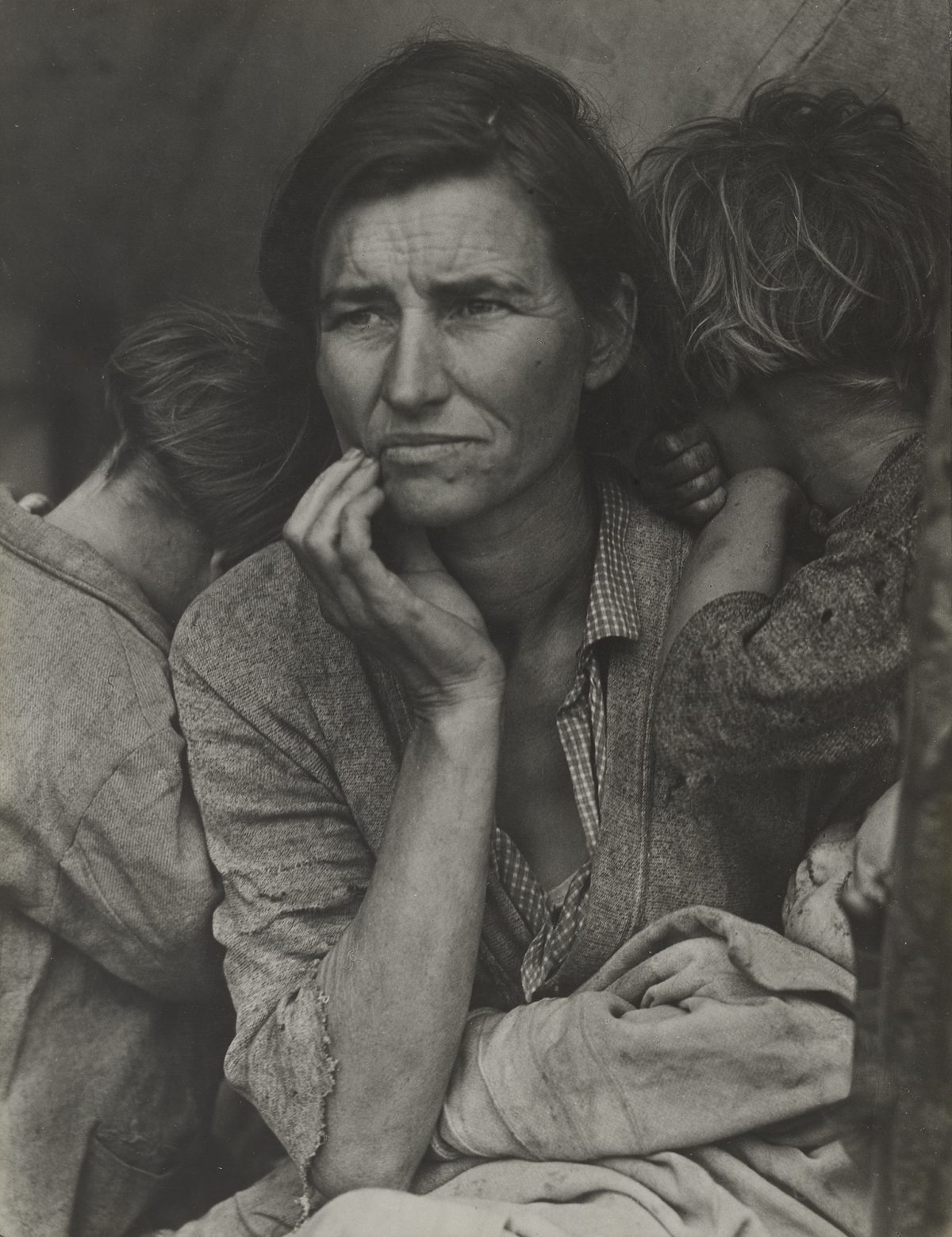

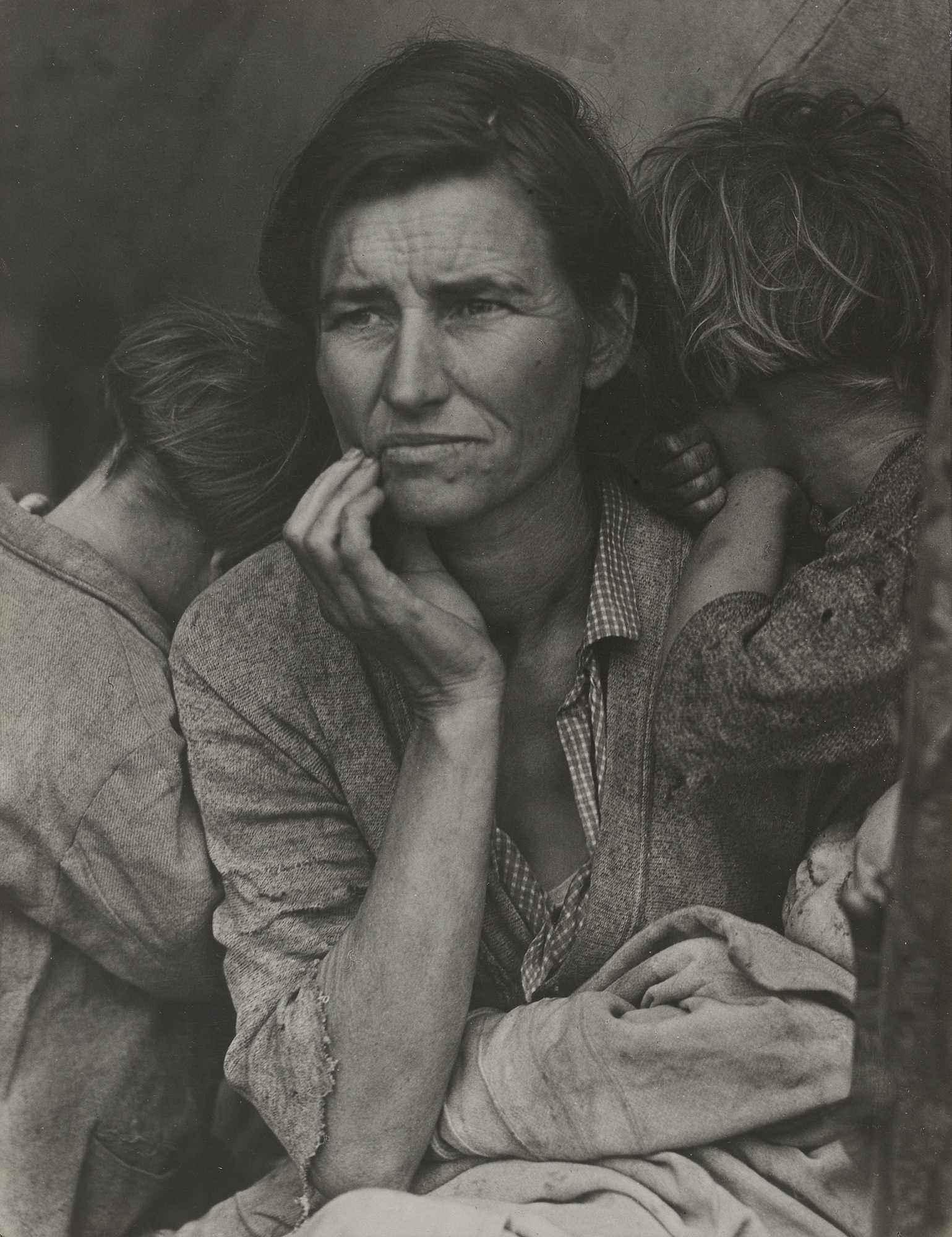

Ses yeux sont perdus dans le lointain, comme si son regard était tout ce qui lui restait pour s’échapper de sa condition. Deux enfants l’entourent, le troisième sur ses genoux. Elle doit être jeune, mais semble avoir vécu un siècle. Migrant Mother est la photographie la plus connue de Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). Le MoMA lui consacre jusqu’au 9 mai sa plus grande rétrospective depuis plus de 50 ans, « Dorothea Lange : Words and Pictures »… dans cet ordre. Une centaine de photographies issues des collections du musée, mais également des archives, et notamment des éléments de correspondance, des publications et des travaux universitaires contemporains permettent d’examiner la manière dont les mots – les siens et les nôtres – influencent la manière de comprendre son travail.

Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. March 1936. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 x 8 9/16″ (28.3 x 21.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

Rare photographe a avoir été reconnue de son vivant, Dorothea Lange naît Dorothea Nutzhorn près de New York. Après des études à la Columbia University et des cours de photographie auprès de Clarence Hudson I WHITE (1871-1925), elle décide de troquer la côte Est pour la côte Ouest et prend le nom de jeune fille de sa mère pour ouvrir un studio à San Francisco, en 1918. Dix ans plus tard, c’est la crise de 1929. La Grande Dépression jette sur les routes des milliers de travailleurs en recherche d’emploi, et Dorothea quitte son atelier pour les suivre. Elle est bientôt employée par la Resettlement Administration (devenue plus tard la Farm Security Administration) pour documenter la réalité des conditions de vie des ouvriers agricoles, dramatiquement impactée par les conditions climatiques catastrophiques et le krach boursier. Son premier rapport de terrain a une véritable répercussion, et passe même entre les mains des locataires de la Maison Blanche : une aide d’urgence est débloquée pour aider les compagnons d’infortune du Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona. La FSA, consciente du pouvoir informatif et émotionnel de ce média encore sous-utilisé au niveau gouvernemental, réunit une petite équipe dont émergera certains des plus grands maîtres de la photographie du XXe siècle : Walker EVANS, Russell LEE, Arthur ROTHSTEIN ou Ben SHAHN. L’exposition étudie la carrière de Lange dans un ordre chronologique, des portraits de studio à la Grande Dépression et à son travail pour diverses agences gouvernementales, en particulier ce documentaire accablant sur les conditions de vie des Américains d’origine japonaise, internés dans des camps au lendemain de l’attaque de Pearl Harbor, si dérangeant qu’il fut censuré par l’administration Roosevelt et publié seulement en 2006.

Ses images sont très parlantes, elles rendent l’atmosphère générale, les conditions de vie des portraits, le désespoir et la résignation, l’espièglerie du regard et l’innocence, la colère et la fatigue. Et pourtant leur auteure n’a jamais pensé que ses photographies seules étaient suffisantes. Toute la controverse autour de son iconique portrait de Migrant Mother lui donne raison : on peut faire dire tout et n’importe quoi à une image. Son travail avait une relation compliquée avec les mots, et l’artiste voulait être aussi juste avec son stylo qu’elle l’était avec son appareil. Une lettre à John Szarkowski de juin 1965 reprise dans l’exposition rend compte de cette incessante recherche : « Suis en train de travailler sur les légendes. Ce n’est pas un simple travail administratif, mais un tout processus, car elles devraient non seulement contenir des informations factuelles, mais également des pistes sur les états d’esprit, les liens et le sens. Ce sont des passerelles, et en expliquant la fonction des légendes, comme je le fais maintenant, je crois que nous étendons le champs d’action de notre médium. » Dorothea Lange voyait la photographie comme le principal moyen de son engagement social, choisissant de sauver de l’oubli les laissés-pour-compte et d’informer sur la réalité des histoires humaines de son temps.

Son œuvre rencontre très tôt un large public, car les photographies étant propriété de l’État, elles sont publiées sans demande de paiement ce qui contribue à leur propagation rapide. Près de 80 ans plus tard, la charge émotionnelle est toujours aussi efficace. Les collectionneurs honorent l’artiste de nombreuse enchères en salles de vente. Le marché de Dorothea Lange a connu un rebond après son record absolu de 2005 pour«White Angel Bread Line» chez Sotheby’s NY emporté à 822 400 $. Ce fut une année en or, avec un pic du chiffre d’affaires qui n’avait plus été approché avant 2019. L’année dernière en effet, la transactions se sont accélérées – avec 40 lots vendus contre 12 en 2018 – et le produit de ventes annuel de l’artiste (près de 1,2m$) lui a permis de faire un bond en avant dans le classement mondial, 2300e place à la 876e place. Nul doute que l’exposition du MoMA permet de remettre l’artiste à l’honneur en salles de vente : ce mardi 25 février, Swann Galleries New York propose pas moins de 9 photographies, des tirages attendus entre 3.000 et 6.000$ en moyenne.

Source : Dorothea Lange, faire parler les images – Artmarketinsight – Artprice.com